The average developing country lives off exporting commodities like oil, gas, copper, cocoa or soybeans. The sale of these resources brings both revenue to the government and foreign currency to import what is not produced at home – which, in these places, tends to be most things. So whatever happens to the price of those commodities matters a great deal for development and, even more, for the war on poverty. The problem is that those prices are famously volatile. They can jump up and down seemingly at random, from year to year, month to month, even within a single minute. This makes life miserable for those who have to plan public investments in schools, hospitals or roads. Statisticians and investors have studied the problem to death, not least because there is a lot of money to be made if you can find a predictable pattern. And despite all their efforts, they have come up mostly empty-handed.

Mostly. There has always been suspicion that, if you took a really long view – we are talking centuries here – you might uncover periods of about forty years when commodity prices steadily climb for a decade or two, only to fall slowly back to where they were. That is, you might uncover “super-cycles”.

It may sound crazy but, before anyone could actually find one, plenty of theories were put forward to explain why super-cycles happened and what to do about them. The stories went more or less like this: a technological innovation triggers a period of prosperity in a large, advanced country — after all, they have most of the scientists — and its industries and cities begin to demand more energy and food from abroad. Think of Britain’s industrial revolution in the late 1700’s sucking raw materials from the developing world and you’ll get the picture.

Prices for coal, cotton, sugar, tea and the like go up and greater quantities are produced. But over time, the innovation wears out, demand dwindles right when supply is growing, and the prices of commodities tumble. End of the super-cycle.

Now, all this could have just been a topic of academic banter – fun but inconsequential. Except that it came with a dangerous recommendation to governments in poor countries: try to use the times of commodity bonanza to create local industries, at any cost, even if you have to use taxpayers’ money. Otherwise, you will be left with nothing when the down-turn comes.

Many heeded the advice and followed this path, with disastrous results, from isolation to corruption to inflation. [If you are a Latin-American over 50, you probably suffered through this.] Remember, this advice was based on a phenomenon that we could not see! By the late 1980’s, two Nobel-laureate economists had denounced super-cycles as, well, baloney.

Was it? In 2012, new research claimed to have found evidence of commodity super-cycles. What’s more, it suggested that we may be in the middle of one as we speak. The claim is based on two methodological break-throughs. One is better and longer data. The other is a statistical technique called “the band-pass filter” – you really don’t want to know, but think of it as playing with your camera’s zoom until you get the right photo of your son’s entire soccer team. Put the two together and it turns out that, over the last one hundred and fifty years, the world has been through three complete super-cycles, each about four-decades long, and each making commodities between 20 and 40 percent more expensive, before prices dropped back to their previous levels. They all took place around major shocks to the global economy: World War I, Europe’s reconstruction after World War II, and the Arab oil boycott of the early 1970’s.

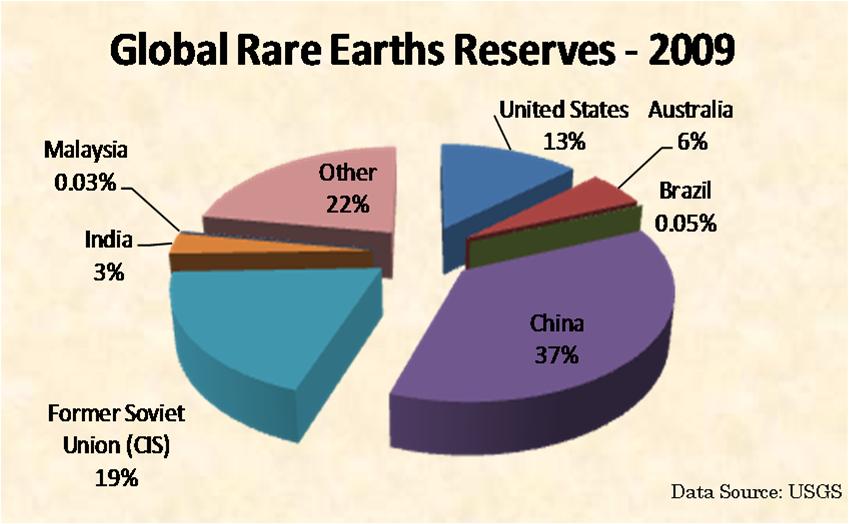

But the new findings shed light on other, more current questions. First, we are in the upswing of another super-cycle right now. What is driving it? In a word: China. The new economic super-power’s appetite for commodities has been raising their prices since the early 2000’s. No surprise there. More exciting, we may still be half-a-decade or so away from the peak—barring out-of-the-blue crises, of course.

Second, is there a very-long-term decline in commodities? Except for oil, probably yes. Controlling for inflation, during each super-cycle the average price of commodities has gone down, in some cases by a lot – metals and agricultural products have fallen by about a third and half, respectively, over the last century and a half. [Hard to believe, but back in the mid-1800’s most commodities were much more expensive than today]. Oil, on the other hand, has tripled in value.

Third, are new technologies for exploration and exploitation increasing the speed at which we can find and extract oil, gas and minerals? Yes. From airplane-mounted detectors to fracking, we no longer have to wait for decades before supply responds to demand and larger quantities of commodities reach those who want to buy them. Ergo: when the next down-turn comes, prices will fall faster than in the past.

Finally, and perhaps the most important question, should developing countries try to use their commodity income – while it lasts — to build industries? Surely diversification has huge benefits. You don’t want to depend on one or two natural resources that, anyway, generate few jobs. But that’s true regardless of super-cycles. And it does not necessarily mean more factories and mass production, good as those may be. Different from the times of industrial revolutions, modern economies prosper on services and cutting-edge technology. The real trick is to translate the upswing of the cycle into human capital and knowledge.

By Marcelo M. Guigale (Economist at The World Bank)